What Is a Department Managerã¢â‚¬â„¢s Objective in Reviewing the Departmentã¢â‚¬â„¢s Staffing Mix?

Keywords

Wellness system reform, Healthcare management, Organisational transformation, Economic crisis

Introduction

Health arrangement re-organization is a common approach to healthcare reform aimed at better managing demographic shifts, changes in the health-burden profile, healthcare technologies, public expectations and the need for efficiency and sustainability in wellness service delivery [1,ii]. In line with international trends the Irish health system is undergoing major re-organisation. Some of these changes are driven by the desire to evangelize on policy commitments while others are oriented towards greater operational efficiency and coherent service delivery. These organisational changes come on the back of the international fiscal crunch and its negative touch on on health reform in many European countries [2]. This impact, although rooted from 2008 when Republic of ireland reached fiscal crisis indicate, became conspicuously credible in 2012 when indicators of health resourcing and performance showed the wellness system doing 'less with less'[3]. Since 2008 wellness funding was cut by €1.7bn and 12,000 whole time equivalent positions were taken out of the wellness service. The financial crisis contributed to a health resourcing crunch which in turn farther complicated an ongoing organisational crunch. This crisis was manifest in the difference of loftier calibre professionals from the wellness organisation, absence, low staff morale, a blame civilisation, lack of investment in engineering science and direction systems, and greater levels of bureaucracy, fragmentation and change-fatigue – all outcomes reported in our data.'

These organisational weaknesses evoke some of the failures identified past the Mid-Staffordshire Written report [4] and influence concerns for managing patient prophylactic and quality of care, the ability of the organisation to remain within budget and importantly, to evangelize on fundamental reforms [3,v]. The concern of this paper, taking this context into account, is to appraise health system capability for transformation during financial and economic crisis from the perspective of health service managers'. We do this by identifying the priorities, challenges and expectations of health service managers as they work through economic crisis. Nosotros and then appraise the potential touch of these perspectives using an organisational readiness lens.

Methodology

Conceptual Framework

Previous piece of work assessed the resilience of the Irish Health arrangement in the face of economic crisis, health budget cuts, cost-shifting from government to households and negative performance indicators [6]. This paper develops that analysis by highlighting how healthcare managers' priorities, challenges and expectations, impact on health system adequacy for transformation [7,eight]. Having identified core themes through content assay of qualitative data we appraise capability for transformation past examining emergent themes through an organisational readiness lens. We apply a 4 component readiness model that includes the variables of change valence, change efficacy, discrepancy and principal support [nine]. Modify valence refers to employees' perception of the benefits for themselves as a outcome of the planned change; modify efficacy refers to employees' perception of their adequacy to implement planned changes; discrepancy refers to employees' conventionalities in the necessity of the change to bridge the gap betwixt an organisation'due south electric current and desired state; and finally principal back up refers to employees' perception of the delivery of formal organisational leaders to support the successful implementation of change.

Data Generation Tools

A survey of 197 health service managers was carried out in late 2013 for which 81 responses met the inclusion criteria generating a response rate of 41%. Respondents were asked to identify government reform priorities, likewise every bit their ain managerial, priorities and to calibrate the fourth dimension they spent on implementing or promoting these. To allow for comparison of prioritisation and time allocation, the research team developed indices from individual responses which revealed how important managers think different priorities are for the government, how important they are for themselves, and the time they spent on them. Respondents were besides asked an open-ended question to identify key factors that facilitated or inhibited them in implementing reform.

For more depth of analysis, eighteen qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted with senior managers from across the Irish wellness organization during the period of 2011 to 2014. This newspaper focusses on the second wave of these conducted in 2014. NVIVO software was used for content analysis and identification of core themes.

Results

Health reform priorities survey

Survey results emphasise the multiplicity of priorities for health service managers. Nineteen unlike themes were classified by at least half-dozen managers every bit beingness a priority for regime. The peak 5 were:

1. Reducing waiting times in emergency departments

ii. Transferring care from hospital to the community

three. Living within budget/austerity measures

4. Money Follows the Patient

5. Driving down the price of drugs

These priorities do not reflect the headline government reforms at the time but seem to relate to running the healthcare system more effectively in the constrained resource environment. The notable exception is Coin Follows the Patient (MfTP) which is part of the regime reform parcel. Nevertheless, MfTP can also be seen as a way of making the current organisation more than efficient and may be as much about improving organization functioning and efficiency as it is well-nigh health reform.

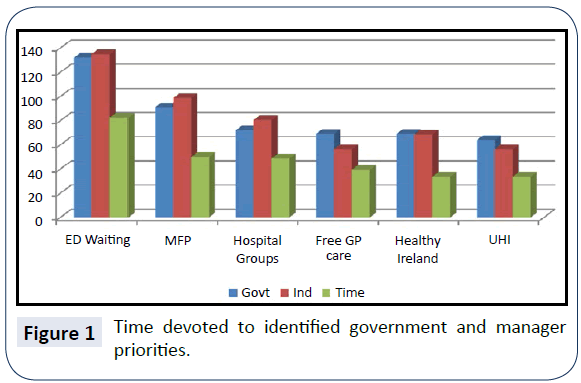

A critical issue therefore is whether the government's headline reforms are getting the focus they require for full development and implementation? Figure i compares time allocated by managers to activities perceived equally priorities for government and managers themselves (Figure ane).

Figure 1: Fourth dimension devoted to identified authorities and managing director priorities.

Despite approximately equal scores registering for perceived authorities and managers' priorities, many key reform initiatives are failing to become a proportionate share of managers' time in practice. The lower time allocation is non a reflection of individual managers valuing things differently from stated priorities. Instead it appears that priority reform activities are being squeezed out. To go an insight into what is displacing stated priorities it is useful to review those activities where fourth dimension taken is disproportionately higher.

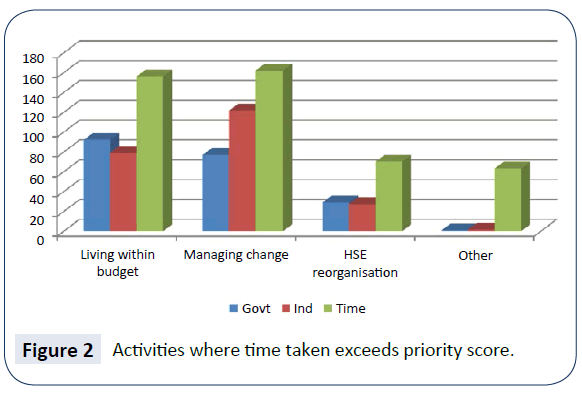

Figure two shows health service managers spend much of their time running the current organization and the immediate enactment of change-projects in the service of operational efficiency rather than the reform agenda. This imbalance occurs fifty-fifty when managers themselves concur that such activities are of lower priority. Managers written report that over 25% of their time is taken upward with 2 activities – living inside upkeep and managing change.

Effigy 2: Activities where time taken exceeds priority score.

Given the challenges of implementing major organisational change during economic crisis and austerity, managers were asked to identify factors which inhibited and facilitated positive alter. Several factors emerge as critical drags on their ability to work finer towards positive alter. These include insufficient resources and tension between the continuous bulldoze to reform and other competing priorities. This dynamic is further constrained past a lack of clarity on the goals of reform and a sense of disempowerment and lack of recognition of the challenges faced:

"There is no recognition that fiscal restrictions, ED trolley wait reductions and scheduled care targets are incompatible after six years of cuts."

The tension is partly due to the scope and extent of priorities and a lack of strategic and implementation planning:

"In that location are too many major priorities ... [nosotros need to] focus on what is achievable."

"Authorities continues to manage change as a result of knee-jerk reactions to detail circumstances. Government policy is developed with no thought given to whether practical implementation is possible - considering government and civil servants practise not have to implement wellness policy, the wellness executive does."

An absence of a well communicated and sustained vision is too identified:

"A clear plan with timelines and milestones would be helpful as the bulk of staff have no real understanding of what the health service will look similar, or when it will change."

"Since I joined the wellness service the organisation has been in constant flux and modify. To date none of the change programmes have been given the chance to bed down."

These inhibitors are noted repeatedly by managers equally failures of acceptable resourcing, recognition, communication and leadership, and are judged to result ultimately in a loss of focus on the patient.

Several factors were identified by managers as facilitating the change procedure. These included squad-working, dedicated staff, re-system enablers (eastward.one thousand. public service agreements and clinical care programmes), increased autonomy in some instances and local noesis and experience. When leadership and vision are nowadays managers feel empowered to participate in the reform process, they value "integrated management [that] listens to other voices and makes the tough decisions."

Content analysis of manager interviews

On the basis of the health reform priorities survey qualitative interviews with senior healthcare managers working in rural, urban, primary and acute wellness care settings were conducted. The focal topic emerging from these interviews is the negative touch of abiding health service re-organisation. This is noted beyond three domains of service coordination and delivery:

1. The re-organisation of service coordination (into divisional directorates)

2. The re-organization of acute intendance (into seven hospital groups)

iii. The re-organisation of primary and social care (into nine community healthcare organisations).

Three cantankerous-cutting themes have been identified in relation to these re-system processes: the negative bear on on patient intendance, further fragmentation of an already fragmented system, and the undermining effect of the weak implementation of reform. The challenge of service delivery in a period of economical crisis is pertinent to all these themes, as will be highlighted below.

The negative impact of re-organisation on patient care

Re-organisation for health service reform is hard but fifty-fifty more so during economic crunch. We note how managers link non simply the reduction in resources, but also the establishment of divisional directorates at health service corporate levels with a breakdown of established patterns of patient care. Respondents believe this organisational change is disrupting practiced working relationships which facilitate the flexible direction of patients with complex care needs beyond healthcare domains. Natural links betwixt the hospital and the primary intendance service are severed. A number of operational links between infirmary and customs (e.g. referral paths and local mechanisms for coordination) are threatened due to the establishment of the bounded structure.

"My real fear is for directorates – I'm in a organisation that's already quite fragmented; putting those silos in, i.east. directorates silos should really just be a top layer on a whole system, nosotros'll cease up pushing our clients. Information technology may arrange the budgets and it may conform management, but it's not going to suit the clients". In a tight monetary climate results and efficiency-orientated organisational models can event in negative patient outcomes and a weakened civilization of care [4].

Along with the creation of the divisional directorates, respondents were also concerned for patient intendance on the basis of reduced resources, both staff and funding. During the crunch managers were expected to meet outpatient waiting list targets with significantly less staff while increasing new services. Respondents pointed out that with the new pressures of population change (increasing numbers of older, chronically sick patients as well every bit general population growth) condom and quality of care is a large challenge. With staffing numbers down and existing staff under growing stress, managing risk was identified every bit increasingly difficult and of deep concern. As 1 respondent noted, "efficiency is being pushed to the limit". On the basis of this analysis two sub-themes underpin the negative touch on patient intendance as a result of reorganisation – established care patterns (such every bit they are) are under threat, and limited resources are putting patients at risk.

Further fragmentation of an already fragmented system as a result of re-organisation

The theme of fragmentation breaks downwardly into three sub-themes, fragmentation in terms of upkeep and funding management, fragmentation in relation to homo resource and staff wellbeing generally, and finally issues relating to arrangement functionality and fragmentation – the latter two being of greater significance than the first. In 2012 infirmary managers faced "a tsunami of cuts" while being required to increase productivity and improve services. For voluntary hospitals funding levels were uncertain due to a reduction in privately insured patients and insurance companies withholding payments. The pressure to come across upkeep targets at year-finish resulted in considerable financial challenges including managing large overdrafts. Beyond these operational concerns the key difficulty identified for the emerging structure was the absenteeism of a machinery that results for managing budgets across the divisional domains. While none of these issues may seem directly related to fragmentation as such, the loftier levels of financial doubt undermine the sense of cohesion, conviction and resilience within the system generally.

Fragmentation resulting from human resource and staff wellbeing challenges characteristic strongly in respondent's comments. Staff shortages affect on patient outcomes and the ability of managers to control waiting lists. These were due to a range of measures including a policy of voluntary redundancy, a lack of stable appointments especially in urban settings, senior managers leaving the system, high levels of absenteeism and a moratorium on civil service hiring beyond the public service. Also as identifying a lack of skill in working with new direction systems and processes, respondents too noted how staffwellbeing is under threat with some managers reporting a sense of isolation and frustration at the lack of recognition past senior management or politicians of either the gravity of the challenges they were facing, nor the successes they achieved in a difficult climate. Respondents noted that although some of the challenges are systemic (e.g. trade union intransigence changes in service delivery practices, a general work culture embedded in disciplinary boundaries making the system inflexible and unresponsive, and a high level of HSE bureaucracy and tardiness in decision-making) their bear upon is more divisive in a period of economic crisis.

Of particular notation in relation to the complexity of managing the different disciplinary boundaries within the organization, one respondent noted

"I think working with clinicians is a big challenge; to get them to move on the alter agenda, because they like to work within their own environments. A lot of our endeavor has been actually getting clinicians to change the style they do things. We can get a situation where the whole organisation is up for change, modify in processes, only the clinicians, either individually or as a group, have the power to … thwart change." The final set of issues relating to fragmentation is the most complex because it refers to organization level challenges. The central topic of concern is the impact on patient care of the new divisional structure of the health services every bit mentioned to a higher place – but autonomously from the threat to patient direction between hospital and community (integrated care), respondents likewise noted how a bounded construction is breaks obvious links within a geographical expanse, sucks human resources from the periphery to the centre, pushes the management of care pathways lower down in the system where at that place is less capability to bargain with them and creates situations where care delivery changes are implemented in isolation without knowledge of their impact on other settings or system levels. In creating infirmary groups as was done in the Irish system, despite some positive outcomes identified, in that location are real concerns about the de-coupling of astute, primary and community care. For some respondents the identity of pocket-size hospitals tin can be put under serious threat, and it was besides noted in ane hospital grouping that a "pressure cooker" situation has been created since the group does not have the capability to serve the needs of its designated population. Organisation level recurring patterns creating on-going fragmentation include a lack of communication and coordination that results in isolation and frustration. Confusion in the reporting structure characterises the lack of communication, as do full general hierarchy and a lack of vision. Respondents talked almost the impact of a blame civilization and "fire-fighting" that takes energy from strategic piece of work. Aggression within the feedback loop is also identified "from politicians to patients" and undermining whatever sense of confidence in attempts at health reform. This competitive arroyo is often associated with performance targets and reporting, and a lack of understanding nearly how to manage the expectations of different stakeholders: "Within a hospital yous've got mixed cultures, you've got professional person groups, doctors, nurses, healthcare professionals, support staff, trade unions, professional bodies, things like the regulators, Medical Quango, etc. So you've all that pot of things going on inside the organization and you lot're trying to manage pathways through that".

These multiple and complex forms of fragmentation contribute in turn to the difficulty of generating positive organisational change and health service reform.

The undermining outcome of the weak implementation of re-organisation

The final core theme is the effect of the weak implementation of re-organisation for health reform; 2 sub-themes underpin this theme. The first of these reflects a lack of attendance to the modify procedure itself within the system and the ensuing confusion this causes. The second pinpoints a lack of systemlevel planning in relation to the implications of re-arrangement and farther highlights ho-hum-delivery on key reform components; features which undermine the direction and procedure of change.

Managers practice not have a sense of conviction and trust in reorganisation processes. They report a lack of clarity about the timing and staging of planned changes; a clarity that would enable them to drive and embed the change. I important barrier in this sense is political instability such that implementation of planned changes is non assured, every bit 1 hospital group CEO remarked, "I sometimes call back; is someone going to saw off the plank behind me?" A culture of blame and scapegoating also impacts on the situation equally front line staff are cagey and chance averse. Managers are stressed and unwilling to "become the extra mile". They report a lack of back up from senior leadership in general, and a lack of recognition of the challenges they face up. This dynamic generates a sense of instability in a context of abiding change which is experienced as a negative spiral. The seemingly unending process of re-organisation that has characterized the Irish gaelic Health system since before 2005 has impacted on the power of people within the system to believe-in and implement those changes.

Along with a lack of trust in the process there is likewise confusion. The budgetary environment remains unstable. In that location are systemlevel changes, office-changes and increasing hierarchy and reporting requirements; all factors generating more "grey infinite". Managers reported a lack of clarity most how to accost headline delivery bug (eastward.g. ED wait times) and a lack of interest in these problems from senior leadership. In that location is confusion near lines of connection (horizontal and vertical) within the divisional structure, and peculiarly about how the hospital groups are to continue forming in practise. Across a range of challenges that include – the governance pathway towards hospital groups, the position of the hospital boards within these, the status and identity of voluntary hospitals within the groups, the all-time sectionalisation of roles, responsibilities and service delivery domains, the pacing of modify and the maximizing of the potential of new structures – the power of personnel to deliver is undermined:

"Our workings with the [Group], trying to find out where we work with regard to that and I suppose the whole governance attribute with regard to that is very, it's very challenging considering in that location is no roadmap … nosotros were just told we're reporting to the CEO with regard to finance and nosotros've never even received anything on paper with regard to that … information technology'due south just a given and that's information technology".

There is a tension for managers in responding to the vision of service delivery articulated at the 'centre' of the organisation while seeking to maintain what is working well at the 'periphery' in local service delivery contexts throughout the land. Managers practise not experience included in the planning and implementation process, ideally requiring a lot of positive communication, empowerment, participation and relationship edifice. The changes need deep-seated mind-shifts and as such managers feel they should exist included more fully. They besides experience these changes (such as integrated care delivery) should be modeled at senior divisional directorship level (e.grand. integrated reporting to unlike divisions).

In that location is a sense amidst managers that the implications for service commitment arising from the re-organisation projects in train' are not well idea-through at senior level resulting in wearisome delivery on change. For example managers highlight how in that location is a lot of focus on managing trolley numbers in emergency departments without proper resourcing of integrated intendance plans. The rationale of the re-system process is non practical in all its component parts and there is underinvestment in terms of the necessary capital and human resourcing required. For case, the highcalibre people needed to evangelize the planned changes in practice are non recruited, as one HSE hospital CEO noted, "public wellness management is a dirty word". In sum, a credibility crisis exists due to the ho-hum pace of change, it'south under-resourcing and its lack of coherence.

Taking into account the experience of senior healthcare managers reported hither in relation to the consequences of the divisional structuring of the wellness service for integrated care, the lack of resourcing of both service delivery and the change process itself, the various sources of on-going and increasing organization fragmentation, and the confusion and lack of acceptable management of health reform and re-organisation processes generally – the capability of the health organization for real transformation seems weak.

Organisational readiness every bit indicator of transformative potential

We now examine managing director priorities, challenges and expectations using the organisational readiness framework highlighted earlier for which change valence; change efficacy, discrepancy and primary back up are key variables [9]. Managers' perceptions of the re-organization processes going-on are an of import factor in determining the outcomes of those processes at system, unit and individual levels. Assessing organisational readiness helps determine health system change and reform potential given that organisational transformation requires perceptional besides every bit practical change [x].

Change valence

None of our respondents identified benefits for themselves in describing the re-organisation process autonomously from ane health service hospital CEO who valued how the infirmary group had been successful in securing permission for limited recruitment. When asked what disquisitional changes would make a real difference managers talked principally of changes in advice – its form, type and touch on. Given the confusion, lack of clarity and low level of confidence nigh organization reform reflected in the information; it seems that the work to enable managers to identify beneficial outcomes for themselves or their teams is not taking place. The notion of modify valence is interesting in that it cites leverage for change in the sense of perceived benefit, as judged past those well-nigh closely connected to the modify process in practice – the managers of the system and their colleagues. There is not only footling sense from managers of this leverage being generated through the re-organization and reform process, but seemingly a lack of adequacy within the organisation to create the conditions through which empowerment can take place.

Modify efficacy

Modify efficacy denotes employees' perception of their own adequacy to implement planned change. Both in earlier interview stages [xi] and in the phase of interviews analysed here, managers doubt their capability to implement a whole range of change initiatives. Time and again they cite limitations within the system, in terms of skills, opportunity and extrinsic factors, such that implementing real modify is judged improbable. Managers also talk of the failure throughout the crisis to resources change through strategic recruitment and training for leadership and management. Despite noting the goodwill of healthcare staff in "going the actress mile" managers seem to believe that their adequacy is insufficient for the changes planned.

Discrepancy

Although managers clearly place dysfunctionality throughout the Irish healthcare organization, it is non articulate that this belief translates into confidence for the necessity, or direction of the various re-organization projects in train. At that place is discrepancy non simply betwixt what different stakeholder groups view as the way forward, only more fundamentally in terms of whether a articulate vision has been articulated at all. Managers interviewed did not seem to have clarity most a 'desired state' for the health system nor about the path towards this state. They speak rather of lacks of understanding, support and communication. While there may be recognition that change is needed – in that location is no sense of shared vision or of the participation required so that employees tin translate and embed the principles of the planned change into local service delivery contexts.

Primary support

The effect of leadership emerges strongly from the information – both survey and interviews. Whether criticized as inculcating a culture of blame, scapegoating or disinterest, or being cited for a range of lacks from communication, to vision, to clarity of purpose and capability, managers do not seem to believe that the level of principal support required for re-organisation and reform exists. There is a lack of confidence amongst managers nigh how much leaders are committed to serious implementation given their sense of the limitations of, for case, the political cycle, the focus on quick or popular wins (e.g. look times), the failure to heed and empathize the challenges managers face, and the failure to properly resources the change process itself. Our analysis suggests that sustained commitment to empowering employees at all levels to own and embed the new structures, processes and management systems is a critical determinant of reform success [12].

Given this assay of little or weak organisational readiness for modify it seems that transformational change, particularly in a context of economical crisis, is unlikely. For transformation reorganisation alone is bereft; attending to the consequences of re-organising actions and more importantly, changes in the underlying meanings of professional work are also fundamental [ten]. The re-organisation processes going on in the Irish gaelic context may indicate a tendency to practice 'organisation or structural alter' in the confront of crisis rather than analyzing what actually needs to change, i.e. embedded cultural habits – the impacts of which are reflected in the research data. There are currently new initiatives in the Irish Health Service to address behavioural and cultural change, merely it remains to be seen equally to whether these can make a significant bear on. Arrangement or structural re-system is non without cost and tin can be destabilising as reported in our data, "reform is needed just is poorly directed and implemented, information technology sucks the life out of the service". The Francis Written report notes that structural change 'can be counterproductive in giving the appearance of addressing concerns rapidly while in fact doing zilch virtually the really difficult issues which require long-term consistent management' [iv]. Long-term consistent management is not only a critical challenge for the Irish gaelic health organization, but across health systems generally. Economic crisis exacerbates this claiming for which in that location is no like shooting fish in a barrel formula or organisational model.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest a health system failing to generate the resources required for the reform intended with health policy shifts and operational re-organisation in play. Health service managers face a wide range of wellness system priorities, many of which they could non address due to the demands of managing economic crisis. At another level the challenges managers face are primarily organisational, and they seem to accept trivial expectation or promise that the cultural and practical shifts required to alter their organisational realities are possible. The factors inhibiting change offer some insight. Fairly resourcing the change procedure itself by analysing and agreement in new means the "really difficult bug" such that director experience is recognised, communication is prioritised and leadership is developed throughout the system volition go some mode to making a difference. If there is whatever promise of real reform these challenges need to be faced in new means. New forms of communication need to exist learnt:

"At present information technology's well-nigh communication, negotiation, building relationships… if relationships are poor obviously people are going to exist reticent, and even where they're good, if your budget's under pressure there's a danger that people get caught in that style."

Nether pressure level health budgeting undoubtedly will remain a factor into the future; supporting managers in creating new patterns of communication may become some manner towards better outcomes in terms of patient prophylactic, organisational fragmentation and weak implementation processes.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This research was funded by the Wellness Inquiry Board in Ireland under the enquiry project: Resilience of the Irish Health Organization – surviving and utilising the economic wrinkle (grant number: HSR.2010.1 (H01385)

Declaration of Conflicting Interest

The authors declare that in that location is no conflict of interest

References

- Quaglio Thou, Karapiperis T, Van Woensel L, Arnold E, McDaid D, et al. (2013) Austerity and wellness in Europe. Wellness Policy113:13-9.

- Thomson Southward, Figueras J, Evetovits T, Jowett M, Mladovsky P, et al. (2014) Economic crunch, wellness systems and wellness in Europe: bear upon and implications for policy - policy summary 12. WHO Regional Office for Europe United nations City, Marmorvej 51, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Kingdom of denmark: Earth Wellness System.

- Burke S, Thomas Southward, Barry Southward, Keegan C (2014) Indicators of wellness organisation coverage and activity in Ireland during the economic crisis 2008 to 2014–from 'more with less' to 'less with less'. Health Policy 117:275-8.

- Francis R (2013) Written report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Enquiry - Executive summary. London: The Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry.

- Thomas S, Shush South, Barry S (2014) The Irish gaelic health-care organization and austerity: sharing the pain. The Lancet. 383:1545-1546.

- Thomas S, Keegan C, Barry South, Layte R, Jowett One thousand, et al. (2013) The Resilience of the Irish Health System: Testing a novel framework for assessment. Health Services Research Vol 13.

- Weiner BJ (2009) A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implementation Science 4:67-75.

- Attieh R, Gagnon MP, Estabrooks CA, Legare F, Ouimet One thousand, et al. (2013) Organizational readiness for knowledge translation in chronic care: a review of theoretical components. Implementation Scientific discipline viii:138.

- Aarons G, Horowitz JD, Dlugosz LR, Ehrhart MG (2012) The office of organizational processes in dissemination and implementation enquiry. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editors. Broadcasting and implementation enquiry in wellness - translating science to do. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. p. 128-53.

- McNulty T, Ferlie E (2004) Procedure Transformation: Limitations to Radical Organizational Change within Public Service Organizations. System Studies 25:1389-412.

- Burke South, Barry S, Thomas S (2013) Case Study 1: The Economic Crunch and the Irish Health System: Assessing Resilience. In: Hou X, Velényi EV, Yazbeck As, Iunes RF, Smith O, editors. Learning from Economic Downturns: How to Better Assess, Runway, and Mitigate the Impact on the Health Sector. Directions in Development - Human Development. Globe Bank, Washinton, D.Cpp156-lx.

- Davies HTO, Nutley SM, Mannion R (2000) Organisational culture and quality of wellness care. Quality in Wellness Care 9:111-9.

Source: https://www.hsprj.com/health-maintanance/is-someone-going-to-saw-off-the-plank-behind-me--healthcare-managers-priorities-challenges-and-expectations-for-service-delivery-a.php?aid=18322

0 Response to "What Is a Department Managerã¢â‚¬â„¢s Objective in Reviewing the Departmentã¢â‚¬â„¢s Staffing Mix?"

Post a Comment